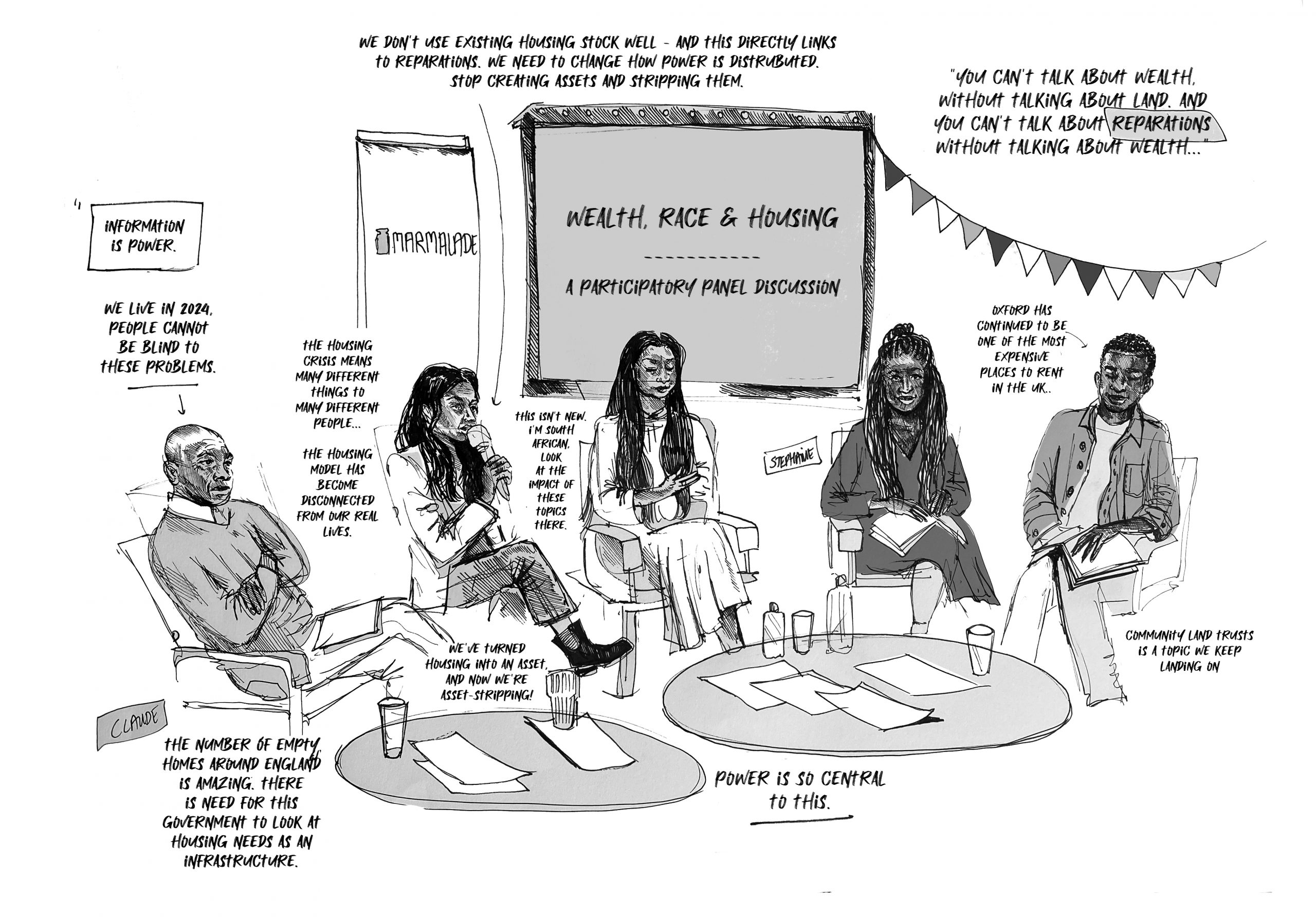

It’s not news to say we’re many years deep into a housing crisis – or that there are no easy answers to solving this. But following our recent Wealth, Race and Housing event (as part of the social change Marmalade Festival 2024), I’m discovering there are reasons to be hopeful about the work that lies ahead.

At the event, our panellists began to untangle the housing crisis knot for us, offering examples of how life in the UK could be different. For obvious reasons, we didn’t plan to solve the housing crisis in 90 minutes, but Claude Hendrickson summarised our intention elegantly:

“There is no one answer to the housing crisis, but raising its profile is the right answer.”

If you’re not yet familiar with our panellists, let me introduce you to:

- Danisha Kazi of Positive Money

- Claude Hendrickson MBE of Leeds Community Homes Ltd

- Angelique Reitif, PhD researcher at School for Policy Studies – University of Bristol and of Black South West Network (BSWN)

- Stephanie Brobbey of The Good Ancestor Movement.

Here is some of what they brought to the table:

1. Hit the brakes on housing financialisation – Danisha Kazi

Danisha is a coauthor of the report Banking on Property – What is driving the housing crisis and how to solve it, and it was so good to have her share some of her findings with us personally.

As Danisha explained, the housing market has become foundational to the whole economy and banking system – an issue which the 2008 financial crisis made plain. Housing in the UK has been turned into something other than infrastructure that exists to meet our needs.

Instead it’s become a person’s primary route to a passive income. A home, Danisha explained, might increase in value by £100,000 over a decade, even if we don’t do anything to maintain it. I might own a house that gives nothing back to society and yet still pays out to me – artificially growing in value in a way that’s totally disconnected from our lives.

It sounds like a good deal, but only to one half of society: the ‘housing haves’ rather than the ‘housing have-nots’. The have-nots, Danisha’s research shows, are typically young people and ethnic minorities: Black Africans in particular have almost no housing wealth at an aggregate level – though that’s not to say that individuals won’t experience a different story personally.

Intriguingly, it’s not only Caucasians but Indians who have the most housing wealth on an aggregate level. As Danisha pointed out, aggregates are always a little distant and unrepresentative, but it raised questions for me – why were Indian migrants able to successfully accumulate housing wealth over time when some other migrant communities weren’t. It’s a question that might eventually lead to helpful answers – so there’s certainly more research here to be done.

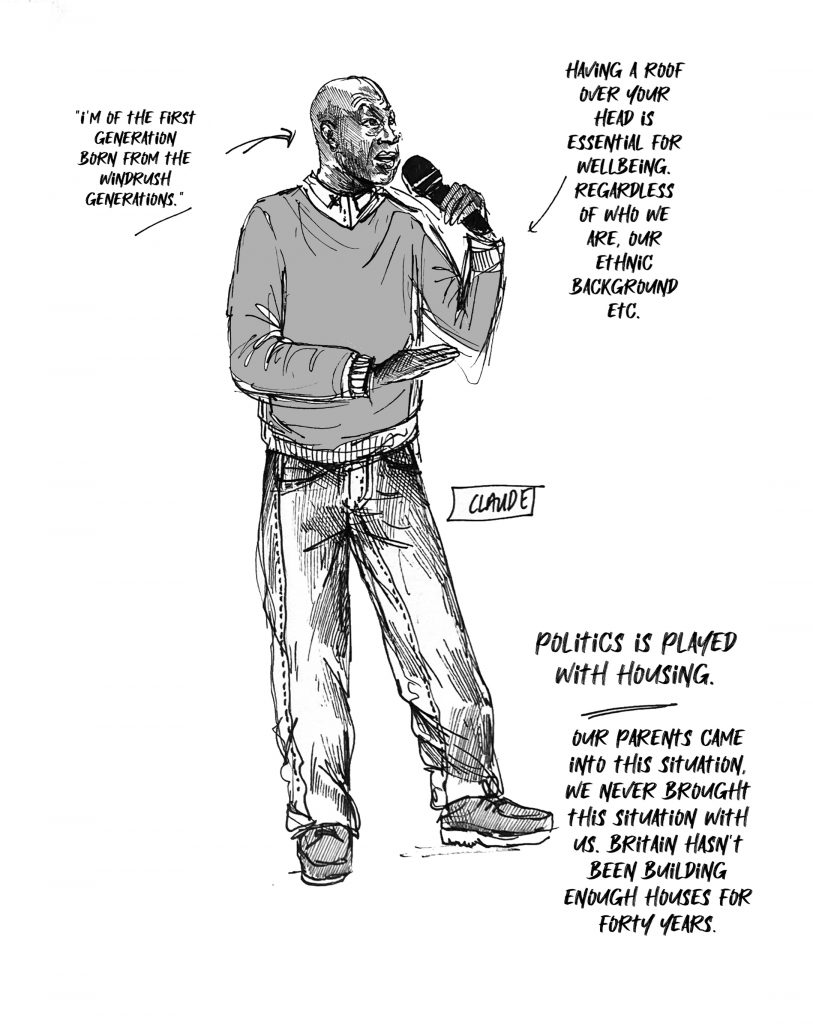

2. We stand to learn from history – Claude Henrickson MBE

Community-led housing, Claude explained, has been a part of both his own history and the UK’s history – even if most of us don’t know about it. 30 years ago, he was project manager on the Frontline community self build scheme in Leeds, in which 12 unemployed African Caribbean men and their families set out to build homes for themselves, laying 92,000 bricks, 52,000 blocks and building 12 semi-detached, two-bedroom houses.

It was a success. So why, Claude asked, hasn’t this scheme been offered to more grassroots communities in the 30 years since? There are no clear answers, it appears.

A child of the Windrush generation, Claude experienced first hand the difficulties of growing up in a postally discriminated area – where housing dereliction brought down aspiration, impacted wellbeing, and even became the cause of riots.

BAME groups, Claude said, didn’t bring this poverty with them – the poverty existed in the 50s before migrants arrived. These poverty-stricken areas are simply where the BAME groups were housed – partly because it was easy to get accommodation there, and partly because the environment was hostile elsewhere. The consequences have now played out for decades.

Claude says he knows he can’t solve the housing crisis by himself, but he can contribute. Following his current research for Leeds University, Claude’s recommendations involve the creation of a new Community Act. This would provide communities with the right to buy, the right to share services and the right to control investments.

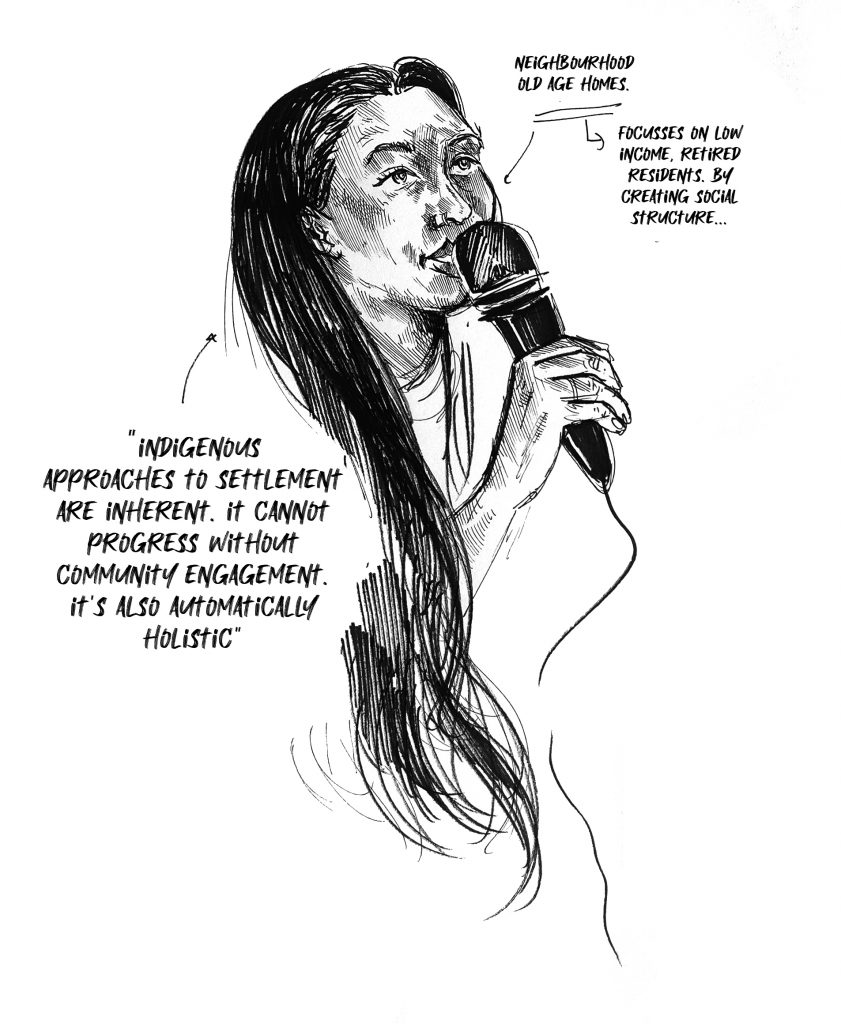

3. We need indigenous inspiration and information – Angelique Reitif

Angelique is a PHD researcher and senior policy officer at Black South West Network, committed to learning from indigenous approaches to development.

Interestingly, she told us of her South African upbringing and what it is like where the housing crisis is even more stark, with a quarter of the population still living in informal settlements. These are areas with 50% unemployment, far removed from critical infrastructure, and the opportunity to access credit to build or renovate is meagre.

Even in this extreme society, however, there are examples of projects working. Most inspiringly, Angelique told us of the approach of the Imizamo Cape Town township that pooled their funds over many years so they could collectively get access to land. The group put together a 100 page plan with roughly 40 pages focused on the environmental approach and 20 on the cultural. The term ‘community engagement’ doesn’t really do the venture any justice and it’s an example that housing groups everywhere stand to learn from.

Closer to home, Angelique found that information is just one more way that people can be disenfranchised when it comes to housing. Angelique spoke of one family of nine in Bristol that lived in a one bedroom flat for seven years and never spoke to anyone face to face about their challenges.

With that in mind the BSWN set up housing clinics, in partnership with Shelter, where once a month people could come to speak to all kinds of housing advisors – face to face. No doubt other parts of the UK will need to see more projects like this.

4. It’s time to leave the extractive economy – Stephanie Brobbey

Stephanie worked as a private wealth lawyer in London for many years, and then, in her words, blew up her legal career. After learning how to help wealthy people accumulate more wealth, she has now set up the Good Ancestor Movement to help individuals to redistribute wealth.

Her work is aligned with the Strategy Framework for a Just Transition, which recognises that the system we’re a part of is extractive from an environmental and social perspective, and often exploitative. As a result, the system is simply not sustainable.

We need to transition to a regenerative economy, Stephanie told us, one where the North Star is ecological and social wellbeing. The Good Ancestor Movement is asking individuals to divest from the extractive economy and start investing in this future vision of the UK where accumulating wealth is no longer our primary goal.

In our Q&A session following her talk, Stephanie said the redistribution of land assets is a key requisite for self-repair. I’ve seen this personally and so, it seems, have many of our panel: it’s hard to accumulate wealth without property, and it’s impossible to accumulate property without wealth. If we’re going to detoxify the housing market, we’ll need some redistribution to take place.

It’s a monumental task but personally I have hope

At Transition by Design, we’re only at the beginning of our research into Wealth, Race and Housing – and I can easily see this initial inception phase turning into a decade of work.

Many questions have arisen for me following the event: How, for instance, can we enable more community led housing, especially for under represented groups? Why have some migrant groups been able to accumulate housing wealth while others haven’t? And how can we complete more projects that could be examples to the housing industry?

The subject of reparations came up at the event – a subject I don’t have time to delve into here. Stephanie and Claude suggested that perhaps we can think less of a past that needs to be accounted for in terms of a monetary figure, and more of a future-facing, ongoing reparative work that needs to be done.

This, I think, is how I am going to move forward. For now, there is work to be done. And I feel energised to face this head on with others on the journey.

Many thanks to the team at Marmalade Festival for the organisation and coordination of the festival, to each of our panel members, to all of the guests that attended, to Jazz Thompson for the wonderful illustrations and to Oxford Atelier for the photographs. I look forward to further opportunities to engage in this topic with wider discussions.