How we as architects and designers can maximise meanwhile use to transform our towns and cities.

Across a number of years we at Transition by Design (T/D) have learnt a lot about transforming empty and underused space into thriving places. We have learnt to turn tight timeframes and shoestring budgets into an advantage, and how to assemble effective teams that know how to listen, collaborate and design with others. We have developed ways to bring our intimate knowledge of design and how humans use space, place and things to the table, whilst considering the potential for positive impact on communities above all else. Alongside other practitioners with a deep knowledge of processes in design, we at T/D are learning what feasibility of a great meanwhile project looks and feels like and where real value can be achieved, and this is knowledge worth sharing.

In part one, we explained why we believe meanwhile use is here to stay. Given that temporary use isn’t going anywhere, we want to help develop a shared field of practice for meanwhile use. For temporary architecture projects to make an impact beyond a clutch of good examples across the country, there is a need for a much greater understanding among us as architects and designers in order to equip ourselves with the knowledge and know-how to effectively make use of the thousands of empty spaces that exist and turn them into impactful projects that vision something different for our towns and cities.

Here are some of the key things we have learnt on our journey towards doing meanwhile well.

Get your ducks in a row

Before you get too far into a project, there are certain key building blocks that need to be solidified. The following are the things that we believe form the foundations of planning for meanwhile use, and without which you’re likely to get lost, waste money or go round in circles later down the line.

Know your impacts: what and who are you trying to make a positive impact on? How can we clarify and work towards these impacts in tangible ways? Think about the people that might be using the space and how to meet their needs, consider the connections to the locale and other secondary users as well as the environment and wider social impacts that might be possible.

Spend in an informed way: With the potential impacts as a basis, think about how you might prioritise spending in order to achieve outcomes. Spending and impacts must be inextricably linked, particularly when it comes to spending on a building that will only be used in the short-term but seeks to have maximum impact.

Use what you have: commit toworking with what exists as much as possible, make do with what you have already and only upgrade if the spending will have a direct relationship on project impacts. Use creativity to find the sweet spot between compliance and good design without always reaching for the cheque book. Sometimes less is more!

Tailor your design: Think about the space you will be inhabiting, the business model you’re following and the wider context in which everything sits. Be specific and set design parameters from the start to carry through the project based on these core elements. A one size fits all approach won’t work as these types of projects will be different each time, but that doesn’t mean you can’t rationalise your approach to make the project both bespoke and attainable.

When setting up Open House Oxford, a talking shop on housing and homelessness, clarifying these foundations before we got started allowed us to find and develop a space which could welcome everyone to come together and have a conversation – from those with two homes to those who have slept on the streets the night before. Once this key aim was defined, we could better work through what elements were worth spending money on, how to tailor the design to this focus, and also how we could find existing spaces and resources that made programming for this outcome feel natural. We knew we needed a space that didn’t feel intimidating to walk into, had a place to have tea and a biscuit so people wanted to stick around, and smaller spaces within the open plan room for conversations big and small.

We won’t say the rest was easy, but at least we had our ducks in a row. Being there for only a year, and knowing what we were trying to achieve, we didn’t spend large sums on partition walls, doors and major changes to the building fabric, but instead got creative with paint, lighting and furniture, tailoring our design and spending. All the while this was coupled with the planned programming with the aim of making the space feel like somewhere anyone could feel comfortable spending time in.

Embrace the messy

If your approach to planning a project is normally rigid, slow and with well defined boundaries, meanwhile projects may require a shift from usual practice. Planning for a short-term project in an existing space is likely to be messy and require a lot of working off the cuff. This shift can create meaningful space for experimentation and learning, and when you are able to embrace the mess and find ways to navigate through it, it can make for some beautiful and spontaneous outcomes.

When taking on a temporary space, things are likely to move quickly. You might be guided by grant-funded deadlines, a pause in the lease payments during building work or landlord timelines. Every wasted day can add up to a decent chunk of the lifetime of the project, so expect the timescales to be a little faster than usual. Project inception to opening may only be a matter of weeks or months in some cases, so be ready to move quickly and roll with the punches, and if things don’t seem ‘finished’ before the doors are open, try to see that as a positive. Consider the potential for delays throughout the design process, prioritise work to make the building compliant and ready for use and carefully design in capacity to pick up loose ends that can be completed in a second phase of works if necessary.

Projects like Caravanserai show what happens when you are willing to embrace the mess, opening a space for trading, sharing and playing in Canning Town with more invitations than fixed ideas. The physical space was completed in tandem with the local community who stepped into the half finished space and filled it with themselves as a way of exploring what it might become. By simply creating a basic structure and then opening the door, Ash Sakula architects demonstrated a vision of an alternative world, grounded in community and imagination whilst still offering a safe and compliant site for people to use.

Given that things might get messy, it’s important to define key decisions early on, draw some lines in the sand and ascertain where there may be wiggle room. Early decisions can really ease the pressures on a project so that everyone knows what the plan is and when they need to do it. This could be lining up occupants, procuring materials or booking in the builder to start on site. If you can get as close to a definitive plan as possible early on, it becomes easier to communicate, manage expectations of those involved and also to stick to a budget and programme.

Demystify the process

For anyone outside of the room, a project can feel like a perplexing black box which can be a major barrier for allowing users and the public to feel like they can take part. Making what is happening as transparent as possible and letting people know how and when they can get involved in tangible ways can increase impact and value from the get go, and start building networks even before you open the doors.

Always include people – as many people as possible, in the process. Get local people’s imaginations working towards visioning what the space can be, invite their curiosity and find ways of capturing their insights. It might seem impossible to distil all the information and take everything on board, but if you set clear parameters for engagement from the start, it will create a far better design overall and leave you with a sense of shared ownership over the space and a network which will stand you in good stead when you’re up and running. We love to think about and develop ways of actively including people meaningfully, with workshops, toolkits, community champions and co-design being powerful tools for collaborating.

Map out the key stepping stones and make them visible. Communicate constantly and make sure it’s a two way conversation. Many of our favourite meanwhile projects have built impact by designing prototypes and workshops that make a project permeable for anyone that could be involved in future or has useful insight. Like our plan for homelessness accommodation that involved people with lived experience throughout the design.

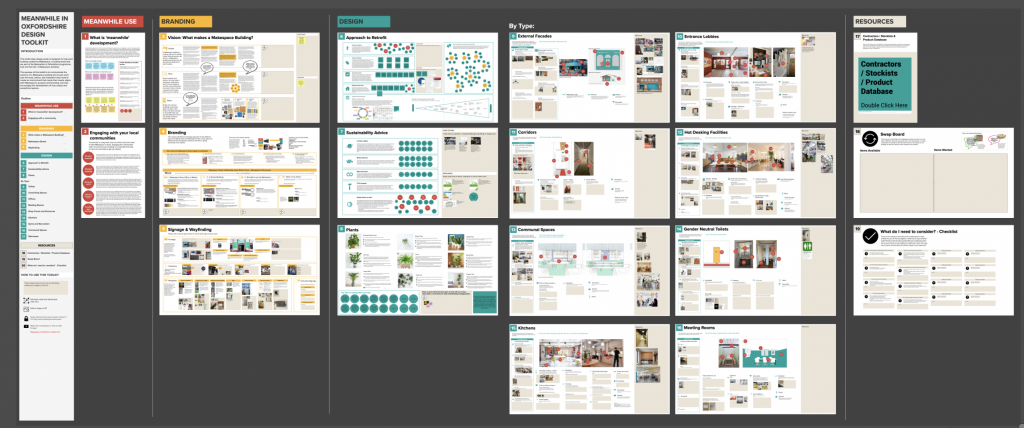

As part of the Meanwhile in Oxfordshire project, T/D formulated a Design Toolkit to make sense of planning to take over temporary premises. It outlines the process, principles and key elements of making a successful meanwhile project open and transparent, as well as being an interactive tool for collaboration. What we include in the toolkit is not rocket science, but displaying the process in this way can really change the way that potential occupants, contractors and the public understand what is going on and shape the way they feel about it.

Build a team that ‘gets it’

At T/D, we’ve had the experience of building teams to deliver different types of meanwhile projects, and we know that when you find a team that understands the brief, knows how to problem solve and collaborate and move quickly, it makes a world of difference.

Contractors and consultants that understand how to approach a build which is only going to be in place for a short amount of time aren’t always the norm, so seek out the right kind of partners and sound them out to see if they’re willing to get stuck in, work quickly and maximise small budgets where needed. When you think you have the right people on board, get their insight as early as possible and involve a range of skill sets in early stage development steps like assessing the feasibility of sites, finding solutions to tricky construction problems and analysing potential gaps in compliance.

Find the people who know what you need and when you need it, like architects and building control specialists, but also remember that diverse teams that know how to communicate are often the best problem solvers – saving money and time, and spotting problems long before they become big enough to stop a project in its tracks. Different individuals bring different skills, and when a good team that can draw on these varied skills approaches a problem, the likelihood is that they will find neat solutions to tricky problems with ease. Find ways to share knowledge and collectively problem solve and be ready to explain over and over again what meanwhile architecture is and why it differs from traditional projects until everyone gets it.

If it’s your first meanwhile project, partnering with organisations that have existing networks and have done it before can make a world of difference.

Know the true value of your project

Ascertain how value will be created, and try to build value at every step of the way. Consider how you might measure and evaluate social impact, and bake this into your thinking about success. How can you build social impact during the build? During occupation? And even once your lease is over? Placemaking, developing social infrastructure and building of local resident’s capacity can be key elements to any project but are often overlooked.

It’s possible to use a single project to transform a neighbourhood and change lives, so even if the scope of your project is limited, don’t let the value you create be constrained by the same timeline. Build creative tools for assessing the value you want to create and find ways of monitoring and communicating what you care about to ensure these are embedded from the start.

When Assemble joined the residents that had started the various strands that made up the Granby Four Streets project, they aimed to build value at every step, through capacity and skills building of individuals that were trained and upskilled, and all the while developing amazing networks of collaboration amongst local people that formed the basis of a locally owned business and Community Land Trust. Designing and building dwellings together with residents, involving locals in ownership and design, and handing over the project and associated businesses to the community means that the value is still being produced, many years after the ‘project’ is over. Many types of outcome can be designed into a temporary project, and Meanwhile Space CIC has a long history of developing value in both tangible and intangible ways. Their recent project, The Hithe is a building specifically designed to act as a piece of social infrastructure that connects the old and new communities in the area of Rotherhithe as the cultural landscape changes. The project is built to be an anchor point in a changing neighbourhood and is tailored around the needs of local businesses and people – it offers spaces for business, work, socialising and play, bringing people together.

Look & feel = outcomes

An eye for look and feel is also imperative to creating outcomes. Be it a relaxed festival atmosphere intended to spark conversations such as at Caravanserai, or at the other end of the spectrum, the apparent permanence of Place Ladywell that has created 24 homes for people to live in, despite the site only being available for 1 to 4 years. Architects and designers, with their strong knowledge of aesthetics and spatiality can curate somewhere that feels appropriate and prompts action and interactions in ways that are meaningful for the intended purpose of the site. Take Blue House Yard, which creates cosy mingling space and footfall on a site through space design, lighting and the inclusion of a bus cafe, building the perfect environment to test businesses and new ideas where drawing a crowd is key.

One of the joys of a temporary space is that it can look and feel just that – temporary! Working out how structures can be reconfigurable and have a life beyond the individual project can create exactly the right feel whilst creating outcomes even when the space is done. Take the Skip Garden, a garden and event site that existed for ten years in various configurations and plots throughout the King’s Cross redevelopment in London, eventually finding a new home as a Story Garden outside the British Library. Not only did it conjure up a space that could envision different ways of inhabiting space, it continues to provide a sense of magic for anyone who enters.

Programming, programming, programming

Designing how the building will be used is just as important as the design of the spaces themselves. Never let the design of the space and its intended programming be separate, and always put it at the forefront of design decisions.

In projects like International House Brixton, we see how crucial the skills of architects are in bringing complex, multi-faceted spaces to life, and quickly. Where time is tight and the interplay between programming and spatial design need to be maximised for the duration of a meanwhile lease, architects can facilitate the production of spaces where community and business mix, collaborations are fostered and where people and ideas flow – all from day one. Blue House Yard paints a similar picture, with an array of spaces deployed from sheds to buses to provide opportunities for a variety of functions and programmes, not expecting a one size fits all for potential users. Or The Community Works in Oxford, originally one open space with one function, now a multi-purpose space enabled by permanent but transparent walls, careful placement of furniture, curtains and lighting to subtly divide spaces for multiple occupants at the same time and also at different times of the day.

One of the key ways of doing this when the programme is yet to be defined is to build in as much flexibility as possible. Make elements moveable, modular and reconfigurable where possible to allow for changing plans and ideas. Just be wary of the impact this may make on privacy, noise and access and don’t let it inhibit the core users or purpose of the space.

Architects of the temporary

As communities are adapting and learning about the potential of meanwhile projects to enable the creation of spaces they want to see locally, innovative architects and designers are learning how to design for the temporary too. Working together to find the sweet spot between creativity and efficiency, and drawing on the contextual knowledge and skills of everyone involved.

As practitioners, we have a unique role to play in the process, both by bringing essential foundational knowledge and ways of working in design and construction, as well as the practice of collaborating with people and in statutory contexts. We hope that we’re on our way to an effective field of practice for making use of meanwhile projects for social impact, and we’d love for others to share what they have learnt, as well as what is useful from our learning.

If you would like to find out more or discuss a project you have in mind, please get in touch.