If you’d prefer, you can also read this post on Medium.

One of the lesser talked about features of the latest planning reforms is a suggestion for street referendums on developments. This idea would see 20% of residents, or ten homeowners able to ask their local council for a referendum on a design code for their street.

Created by residents, the design code would be used to determine the size, height, and style of new homes, and to allow homeowners to add extensions. If supported by 60% of residents, automatic planning permission would be granted.

There are many uncertainties about how this idea would work in practice, and how it would fit with the existing infrastructure of participation in the built environment, such as neighbourhood plans. Done badly it risks becoming a tool for more privileged communities to shape places in their own interests above those unable to participate. But done well, this could be an exciting opportunity for local people to shape the places they live.

We’ve been working alongside citizen groups for almost ten years, helping them to be effective design advocates for their local areas. We believe that anyone can be an urban designer but to do this well, in a manner which improves urban areas for all, they need some expert hand holding.

Architects, designers, and other built-environment professionals can play a crucial role in supporting street referendums and design codes. To help others do this well, we’ve put together seven guiding principles for supporting meaningful citizen-led design.

Don’t be afraid of your own skills

Running a citizen-led design process is not asking local people to do your job for you. Whether you are an architect, designer, planner, or project officer, you have skills and technical knowledge that others don’t. You have an important role to play in helping local groups to understand the context in which they are designing, and to help them imagine what they cannot already see.

When we spend time with community-groups, in meetings, workshops or socially, we see it as data gathering. Just like the careful crafting of research questions, we design engagement activities to generate the data we need, and it is then our job to interpret that data into something useful.

We have a box of tools for doing this, including the creation of design principles or local design review panels, or more creative and communicative platforms such as the co-creation of a zine or podcast. Whichever format you choose, remember your role is to translate, educate, and communicate in order for all parties to be able to effectively design together.

Meet people where they are

People are most able to participate when they are comfortable, and often that means going to them. Location wise try to think about hosting events in spaces that already exist and are already frequented by those you are hoping to speak to. If you pick a place, a time, and a format that works for you, you’re likely to attract other people that look and sound like you. Push yourself to think harder and try stepping out of your comfort zone before you ask others to do the same.

The same principle applies to the topic of the conversations you hope to have. You might want to talk about bus stop locations but if your participants want to talk about parking then you need to start with parking. It’s helpful to have a really clear idea of what you need from any one activity so that you can adapt and change your tactics on the fly without letting your facilitation plan hold you back.

Citizen-led design is an approach, not a one-off activity

To do citizen-led design well, it needs to be a consideration at all stages and by all members of the design team. As well as working with participants, you need to be working with different members of the design team to help them consider where in the build programme input could be usefully incorporated and how the design shape could be opened up to include more voices.

You need to communicate constantly, demonstrating to all participants the impact of their input, and always, always saying thank you for effort and contribution. If plans change or some ideas become unviable, you need to explain this to those involved as you go, they are important members of the design team and should be treated as such. It is not until this approach is embedded throughout your project, in people, ideas, and programmes that good quality citizen-led design is possible.

Be clear and honest about the scope of your project

Many people roll their eyes at the phrase ‘community engagement’, and for good reason. If you’ve had the experience of being asked for your opinion, taking the time and energy to give it, and then being resolutely ignored, then you’re unlikely to do it again.

Be open and honest with your participants from the beginning. If you know that a development site will have 600 new homes, don’t try and hide it. Make it clear that this is not up for discussion and instead, find the elements that are still open to influence and focus your consultation on that.

Don’t call it a consultation if it’s not a consultation

There are many reasons to reach out to different communities involved in, or adjacent to a development. Sometimes it is to consult, a process whereby you ask for input from those with local or specialist expertise, and then translate that input into your planning and processes.

However, this isn’t always possible and the intention of reaching out is to either inform stakeholders of updates on the project or issues that will impact them, or to activate a space by inviting people in and encouraging new behaviours. All have value, but all are different and it’s important to be clear from the beginning and set expectations in the tone and content of your communications. Don’t promise people input and agency that you are not able to deliver.

Respect input as labour

Good citizen-led design seeks to centre local knowledge within the design process, and that knowledge has value. Whether it’s knowledge acquired from a university, a book, the street, or the home, if you are asking for input based on knowledge and experience then that must be recognised as labour.

You can pay people in cash, offer vouchers for local businesses, or make a gesture such as cooking for them. You need to consider the question of incentivisation and how the remuneration will impact who participates and how but this should not prevent you from remunerating people’s labour.

Equally if you’re asking for help from a third partner you need to respect their input as labour. You might be asking a local community group for connections or support, or a local business to use their space as a venue. If you can’t pay them, then make sure there is reciprocal benefit.

There is no such thing as a ‘hard to reach’ group

If you’re using the term ‘hard to reach’ it’s because you’re not trying hard enough. Your primary job as a designer working within citizen-led design is to make it possible for everyone to participate; and, if they’re not able to do so, you probably need to rethink your methods.

Consider the following as a starter for ten: What time, and where are you holding consultation events? What is the tone of your communications and what images are you using? Who might this speak to, or not? Are you the right messenger? Could you consider partnering with a local organisation who is better placed to talk to local people?

By ‘hard to reach’ people often mean ‘furthest from me’ and so you need to start from two truths, firstly that it’s your responsibility to travel the distance, and secondly that you might not always be the right messenger. Both of which are valuable to acknowledge, as early as possible.

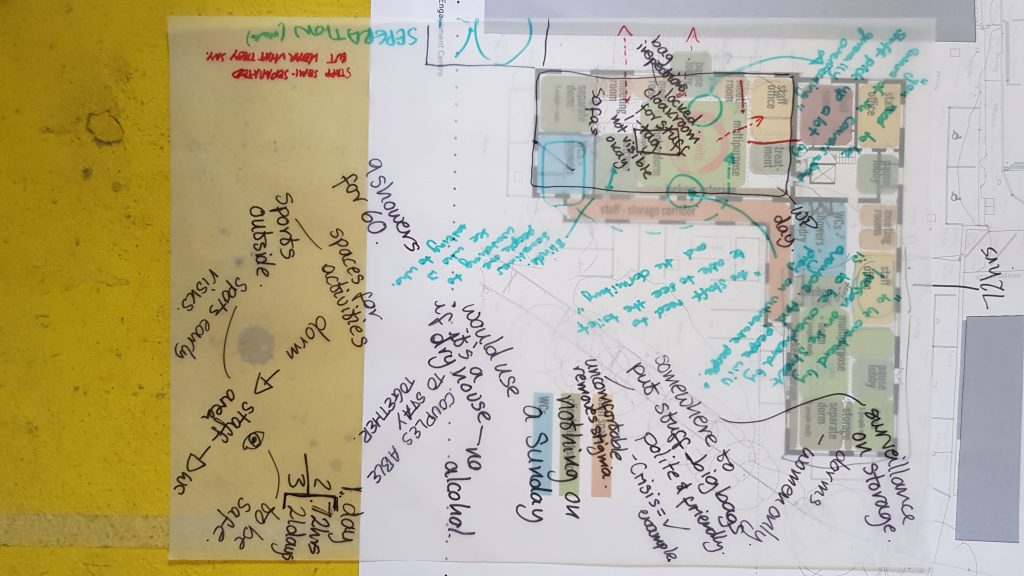

For example, when we designed Floyds Row, we wanted to gather input from those people who were currently accessing services for people sleeping rough in Oxford. As a large, and heterogeneous group, many of whom had a distrust or dislike of anything they perceived to be ‘the system’, some consultation events could get a bit lively. During the engagement events we would encourage participants to speak to each other as well as us, helping them to explore the differences in how they felt and explain key features to their peers. As well as expanding the number of people we could talk to, this ‘peer to peer’ learning also had a much greater impact than anything we could have said.

How can we help?

Citizen-led design, community engagement, and co-design can be daunting. Many perceive it to be an unnecessary and complicated elongator of budgets and timescales but if done well, the benefits to your project can be priceless. In every city we could all point to a project which has gone vastly over budget and timescales reaching into oblivion because of a lack of good quality community engagement. The benefits are clear, and the cost question should really be whether you can afford *not* to do it.

We’ve developed a tool which we call ‘CIA: Consult, Inform, Activate’ to help our clients and the citizen-groups we work with to think through citizen-led design and community engagement programmes. It separates out what we see as the three main drivers for working with local communities and attaches a number of tools to each to ensure good outcomes.

If you’d like to find out more, or discuss a project you have in mind then please get in touch.