This is a longer read, a deep dive into this piece of action research for those interested in our process. If you’d like to explore the findings or read some pithier blogs on housing and homelessness, please head over to homemakeroxford.org.

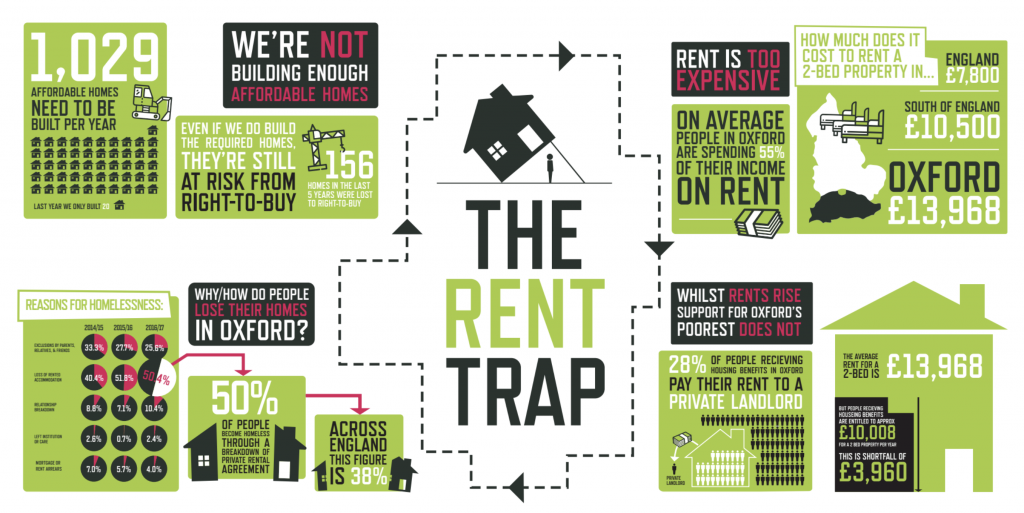

Since 2017, we’ve been exploring (in a round-about fashion) how forgotten, unloved, and sidelined spaces could be used to house people without a home. Faced with a growing need for housing, a stark picture of homelessness in the city, and steadily increased rents, we found ourselves unable to ignore the empty car parks, stalled development sites, flats above shops, spare rooms, vacant homes, underused garages, and other empty spaces that we travelled past daily on our journeys across Oxford.

There were already a plethora of architect-led solutions to homelessness at the time, from the bin-home, to the bench-shelter, to the empty home you could use for post but not to live in. And of course, there was the rise of the shipping container home, purpose designed for inanimate objects and given to humans to live in. As a profession, as a practice, and as a team, we just knew it was possible to do better and so with the support of the David and Reva Logan Foundation, we embarked on an action-research journey to apply our skills in architecture, participatory design, and community organising to ask how these empty spaces could be put to best use.

According to Oxford City Council’s figures, in 2017 there were 3,399 households were waiting for council housing, from a total stock of 7,746 council-owned homes. 1,701 of these were families with young children or who were expecting. Eviction from the private rental market was the single biggest cause of homelessness, responsible for 50.4% of cases. At the time, the cost to buy a house was 17.3 times Oxford’s average annual salary. Council home building was almost zero and homes were (and are) still being lost to the Right to Buy policy. Sixty one people were rough sleeping.

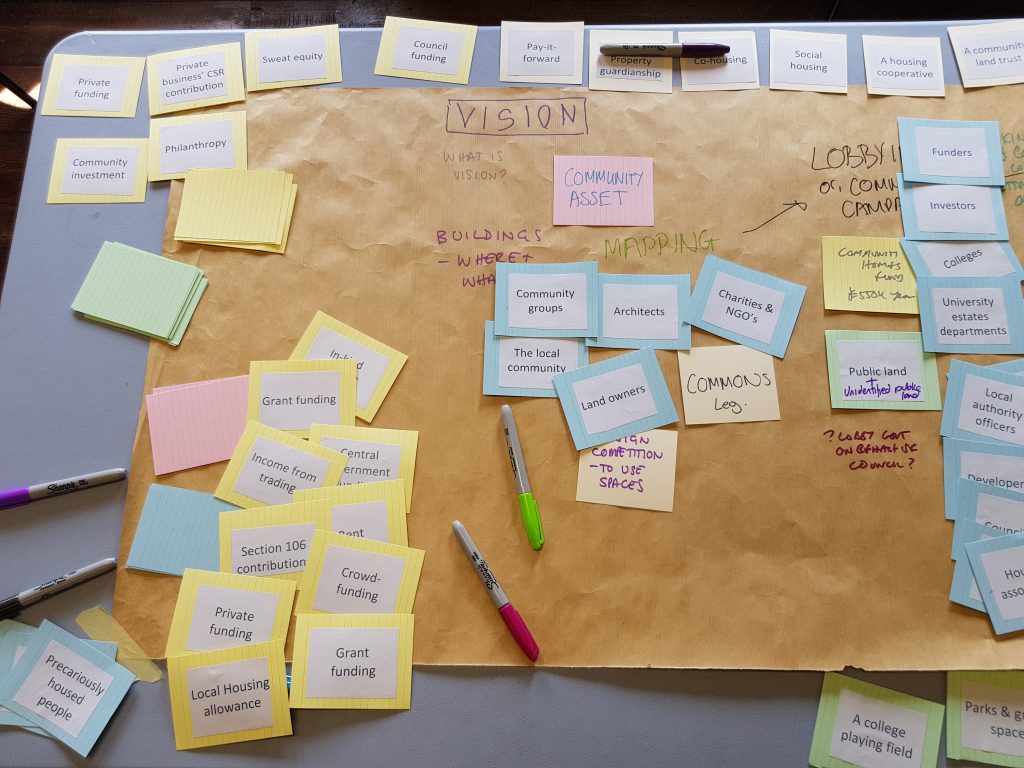

Within this context, and armed with a belief in co-production, a desire for change, and a long list of things we didn’t know, we jumped into phase one, scoping. We needed a research brief, but conscious of ‘knowing what we didn’t know’ we felt others were best placed to write this for us. We brought local stakeholders together, folks with experiences of all kinds including running local organisation, to having been homeless themselves, to those currently working in housing or homelessness, and often a combination of the three. Our question was simple, what should we spend the next three years focussing on?

They told us:

01 “Be ambitious and imaginative!” participants told us that they had almost lost hope for change. Having us come in, outside of the ‘formalised’ homelessness system was seen as an opportunity to breathe some fresh energy into a stagnant system and to demonstrate to some service providers that there were other possibilities beyond the current system.

02 “Move on is not working, and that is blocking up the entire system.” ‘Move on’ is a term used to describe semi-supported accommodation for people who are ready to leave a hostel, shelter, prison, long-stay in hospital or a mental health facility, or any other form of supported accommodation. The intention is they live there for six months to a year before moving on to independent living, either in the private rental market, or into permanent council housing. In reality, because of the lack of council housing, the high cost of rent, and the way in which housing benefit is paid, it rarely works and people are left living in unideal (often shared) accommodation for long periods of time. As well as negatively impacting the individuals, this lack of movement in ‘move-on’ housing backs up the system and causes problems across the board. Participants felt stuck on this and wanted our help.

03 “Alternative models lack credibility, help us build the case” Whilst community led housing and other alternative approaches to private and social renting are established in other countries, participants wanted our help building credibility and enthusiasm for them in Oxford.

04 “I’m just not sure anything other than permanent homes is worth considering?” We found an almost perfect 50/50 split on whether it was worth our time exploring temporary or ‘meanwhile’ home development, for example whereby a stalled development could be used to house modular and moveable homes for a period of up to ten years. We took this disagreement as reason enough to explore both ‘temporary’ and permanent models further.

05 “It’s all about the ‘wrap-around’” participants told us that past ideas had failed because of the inability to consider how a house and its tenant would interact and integrate with their surroundings. Unless the homes we hoped to provide considered in their design where their residents would live, work and play and how they would support themselves to be happy and healthy, they would be likely to fail.

06 “Tell us about housing” participants highlighted a cavernous gap in understanding between those building homes, and those supporting people experiencing homelessness and/or extreme housing need. To produce new housing solutions, we needed to bridge this gap.

We combined what we heard with some of our own research and information gathering and we created seven guiding insights and four research questions which together gave us the foundations of our research brief.

7 Guiding Insights

- Oxford Has Space – we identified a plethora of empty and underused spaces from empty commercial buildings to homes, to stalled development sites and disused garage plots.

- The 10% Gap – we heard anecdotal evidence of the impact of the soaring cost of rent meaning that the cheapest rented accommodation (the bottom 10%’) had simply disappeared, done up and let out to a wealthier class of renter. As the amount paid for housing through the benefit system had not risen, a gap was widening between the supported housing sector and the bottom of the private rental market.

- The private rental cliff edge – renting in Oxford today is expensive, precarious, and often of poor quality. For those expected to ‘move on from ‘move on; into the private rental market, many describe the experience as a cliff edge, one they must navigate carefully to avoid relapsing into periods of poor mental health, or addictive behaviours.

- Tiny houses need bigger ambitions – tiny homes, shipping containers and other such solutions which are designed based on the spatial parameters rather than human need are likely to fail. Rather than starting with a plot size and ‘ideal number of units’, we need to begin with the people, their needs, and how a home can help meet those needs. This includes thinking through how homes interact with the delivery of support services.

- A home rarely solves homelessness – Whilst our research would focus on the delivery of homes, we also wanted to recognise that we had a broader role to play in helping to destigmatise homelessness and raise awareness of the violence of the housing system as a driver of homelessness.

- Oxford knows how to do housing differently – We found a wealth of informed and energetic groups and individuals in the city who were actively involved in community-led housing projects, and campaigning on housing.

- Identities are multifaceted, and so too should solutions be. Different people have different needs for their housing and support services. We found that minority and disadvantaged groups were overrepresented within homelessness statistics and so we wanted to consider how our research might highlight and address this.

Research Questions

- Can a community-led approach provide an alternative method for building good-quality, low-carbon and low-cost housing in Oxford?

- What are the barriers to bringing Oxford’s empty or underused spaces back into use to provide homes for those that do not have them?

- How can we meaningfully include people experiencing housing need in the decisions that are being made about their housing?

- How can we design individual units of housing and the systems that support them in a way that fosters community cohesion, neighbourliness and a shift towards a fairer housing system?

Once we’d set out our brief we got to work. Our research methodologies perhaps look a little different to what you might expect. At the heart of our method is dissolving the boundaries between the research, the researchers, and the researched. Action research is learning by doing, building stuff, talking about interesting things, meeting new people, making new friends, bringing groups together and reflecting and learning constantly.

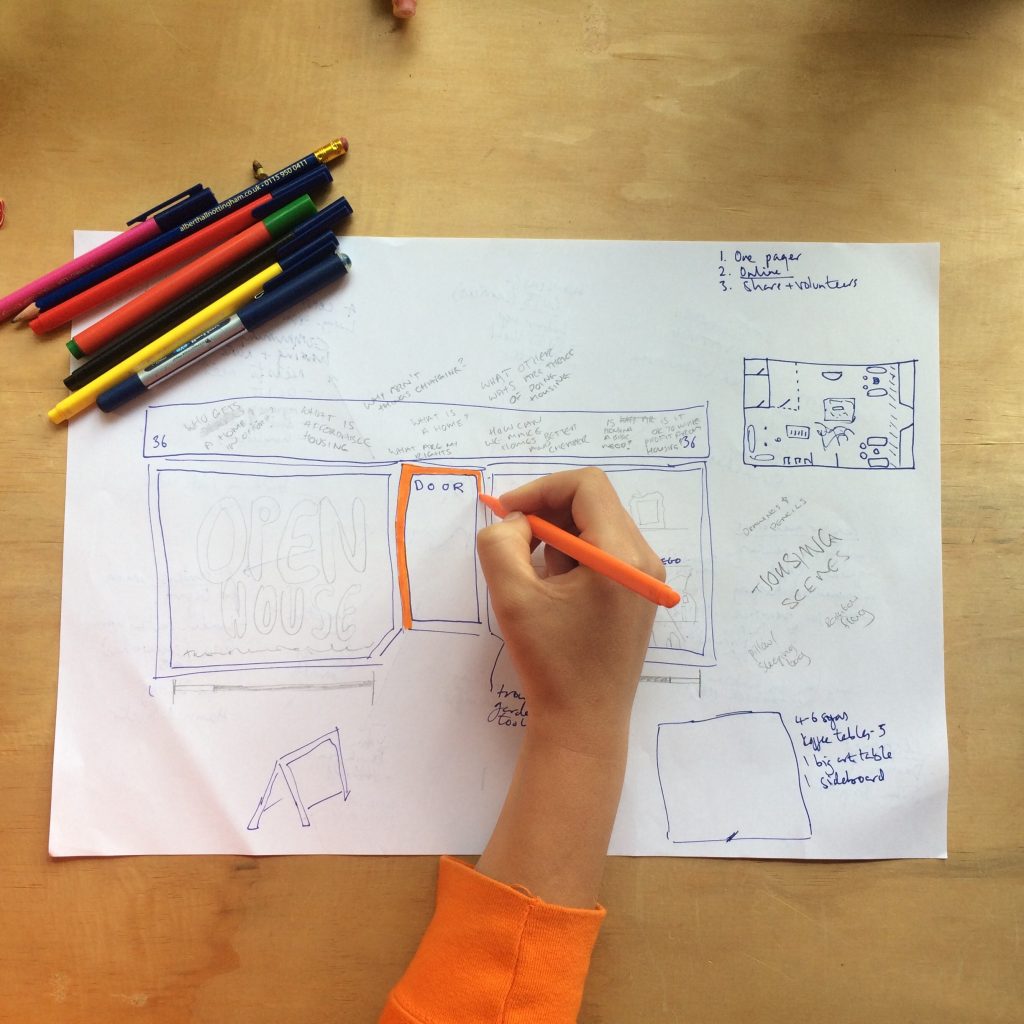

Throughout 2018, 2019 and the beginning of 2020 we ran workshops, chatted to strangers, drank tea, participated in others events and networks, we ran a weekly ‘How to Build a House’ class for Crisis members, we ran a series of panel discussions, we helped build a new homelessness accommodation centre, we did jigsaw puzzles, made zines, wrote poetry, joined protests, wrote articles, spoke at gatherings, and we even opened a shop that sold nothing but stories.

We listened, we created, we played back, we questioned, we presented, we interpreted, we learnt, we presented, we edited, we argued, we learnt more, and at every stage, we tried our best to bring everyone along with us.

By March 2020 we had a lot of new knowledge, a few battle scars, many new friends and contacts, and three big and exciting ideas for how empty and underused spaces could help tackle extreme housing need in Oxford.

- Could we use empty hotels & BnB’s in the city centre (of which we know there were at least 6) to trial a model of move-on accommodation? A model which engaged with the reality of the broader housing system, the lack of affordable housing, and which used a meanwhile lease (and therefore very low rent) as a tool for shifting the business model of semi-supported accommodation to make it easier for residents to move on to independent living?

- Could we develop a toolbox of simple amendments to typical Oxford housing types to make it more desirable for spare rooms to be let-out? And what could we take from the growth in cohousing as a spatial layout and a model for community-focussed living to retrofit neighbourhoods to encourage neighbourliness and the hosting of people in housing need? Along the way, what might we do to provoke a more nuanced but urgent public discussion on under-occupation?

- How could we support Oxford City Council to follow the example set by other cities and embrace modern methods of construction in order to leverage the plethora of empty garage sites as space to build new, low-carbon social homes?

We were excited, raring to go, aaaaaand then the pandemic hit.

Like everyone else our lives got skewed. We had to make sure we were ok, that our families and households were ok, and that our communities were ok. From early on we saw how poor housing design was impacting people’s ability to cope, how the out-of-control private rental market was now causing an acute public health risk as renters were forced to go to work in order to keep their homes, and how vulnerable those living in hostels, shelters or on the street could be to the coronavirus and the broader impacts of the lockdown.

Homemaker had given us knowledge that could be of value and unable to continue with our planned series of Summer workshops, we instead got stuck in to helping the renters rights movement to organise, to advocating for smart housing solutions in response to the pandemic, and in working with Aspire to help open up a series of previously-empty buildings to increase the city’s emergency housing capacity.

We listened as we worked, and along with others in our sector used the pandemic to reflect on UK housing design and the violence that our housing system inflicts on renters, social tenants, the working class, and people of colour.

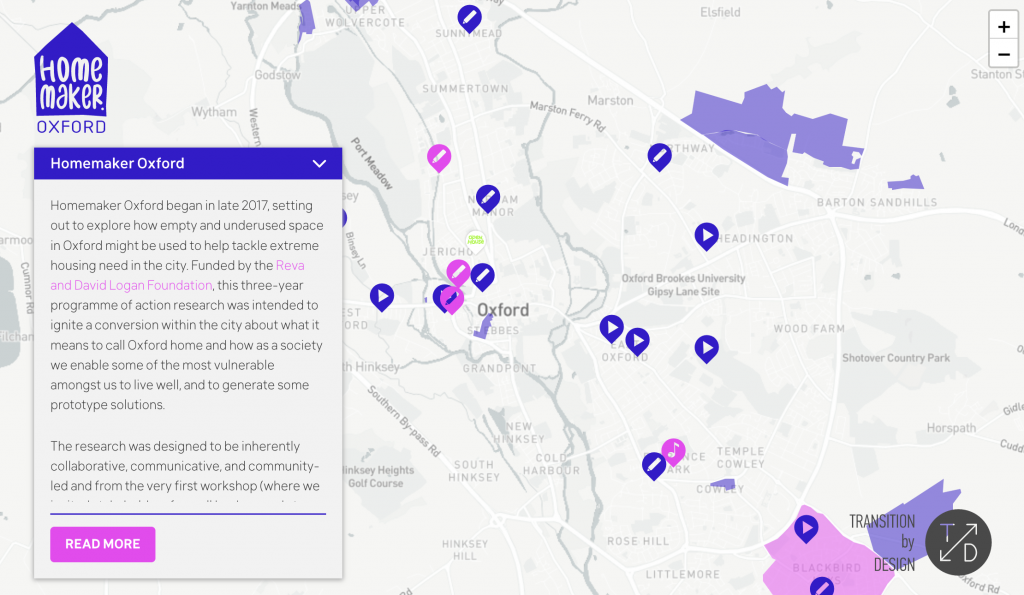

In 2021, still dealing with uncertainties around Covid and lockdowns, we began building a website to host our research.

Homemaker has been a collective effort by everyone who has worked with or alongside us over the years, from activists and campaigners, to local councillors, to committed staff from charities and service providers, and most importantly to those people living in extreme housing need who have taken time to work alongside us. As such, the knowledge built is a common resource and we’ve done our best with this website to recognise this and make the information available and interesting to all.

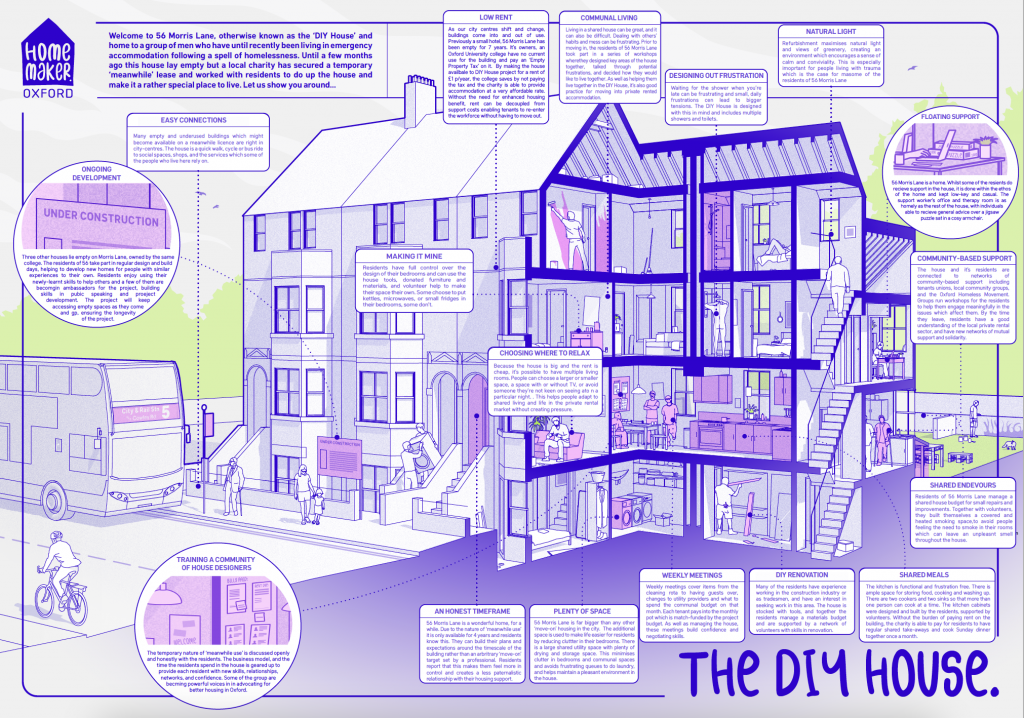

We turned our 3 big ideas into prototype projects, The DIY House, Find the Gap, and Room 2 Stay – and we got started with putting some of the component parts in place to start developing them as real projects.

We road-tested these prototype projects at Marmalade in 2022 and are already working on a number of satellite projects and funding bids to move these ideas forward, alongside some trusted delivery partners.

As our current funding round draws to a close, so does this phase of the Homemaker project. If you’d like to help us take forward any of the ideas mentioned in this article, or on homemeakeroxford.org then please do get in touch.

Homemaker Oxford was funded by the David and Reva Logan Foundation, with additional financial support from Lankelly Chase, Oxford City Council, and The Sankalpa Trust. It was led by Lucy Warin with support from Andy Edwards, Charlie Fisher, Katie Reilly, and the rest of the Transition by design team.